BU earthquake expert says that safer infrastructure can help prevent catastrophic destruction and quake-safe reconstruction could save lives in the future. Around 4 am local time on Monday, February 6, two tectonic plates slipped past each other just 12 miles below southern Turkey and northern Syria, causing a 7.8 magnitude earthquake. It was the largest earthquake to hit Turkey in over 80 years. Then, just nine hours later, a second quake—registered at 7.5 magnitude—struck the same region.

The double whammy of intense shaking collapsed thousands of buildings and killed over 20,000 people, leaving behind a humanitarian crisis in an already vulnerable area. The epicenter of the quakes was near the city of Gaziantep, where there are currently hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees. Aleppo, a city in Syria that has been destroyed by civil war, also felt the brunt of the earthquakes.

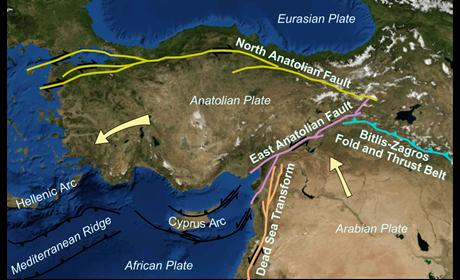

Seismologists consider Turkey a tectonically active area, where three tectonic plates—the Anatolia, Arabia, and Africa plates—touch and interact with each other. The two major fault lines surrounding it, the North Anatolian Fault and the East Anatolian Fault—which has a slip rate of between 6 and 10 millimeters per year—are gradually squeezing the country westward toward the Mediterranean Sea. Yet, many buildings in the region are not built to withstand large earthquakes, according to the US Geological Survey (USGS), making the destruction worse.

Two major faults, the North Anatolian Fault and the East Anatolian Fault, are gradually squeezing Turkey westward toward the Mediterranean Sea, putting the region at risk for earthquakes. Courtesy of Mike Norton, Wikimedia Commons

Why were the two earthquakes so catastrophic? To put their cascading devastation into context, The Brink spoke with Abercrombie about why the region is at high risk for earthquakes and what can be done to warn people about an impending shake before it’s too late.

How do you study earthquakes?

Some scientists go out and measure how much it [a fault] slipped. People like myself are using the seismic waves and their frequency content, because the frequency spectrum contains information about the area of fault that slipped. I’m really interested in what controls an earthquake. We know earthquakes happen mostly on the faults. But there could be a big fault that doesn’t seem to do anything for hundreds or thousands of years. Then suddenly, within seconds, a crack bigger than you can believe moves at speeds of kilometers a second. How do you go from one thing to the other?

To understand the earthquake hazard around here, for example, we have to look at earthquakes that happen elsewhere. Can we take these earthquakes in Syria and Turkey and try to understand what might happen if we had a similar-sized earthquake, which we will, in California? I’m looking to understand how the seismic waves propagate through the Earth, how much energy stays in them as they travel, which is different in different parts of the Earth because the rocks are different. The earthquake itself may be different too.

Once a place has a big earthquake, does that make it more likely to happen again?

That’s something we would like to know. In the short term, we think it’s less likely. It’s hard to imagine how you could have a magnitude 7.8 on that piece of fault again, because there has to be a buildup [of stress] on the tectonic plates for the plates to move. Since they’re only moving at a few centimeters a year, it takes a while for that to happen. For some bizarre reason, if there’s still some slip waiting to happen while everything’s already shaking up, another big earthquake could happen, but usually that doesn’t happen.

What improvements would you like to see as far as how earthquakes are handled?

We’d obviously love to be able to predict earthquakes. As I said, I’m a bit skeptical because you’d still be left with the destruction. Currently, earthquake scientists are working to better their hazard forecasting to prepare people for earthquakes. There’s also lots of work being done in laboratories. Another area of research is improving hazard maps to make them more dynamic, but that is more for the long term so we can see changes with time. At the opposite end of the scale, is earthquake early warning. It’s working in California, Oregon, and Washington, and various other parts of the world. Anyone can get an app on their phone so when an earthquake happens, and the seismometers start to move, they get an alert at speeds faster than the seismic waves travel. This can be very useful to massively minimize damages—it enables emergency services to be prepared and people can turn off their gas tanks, turn off the water, and “drop, cover and hold.” The BART [transit system] in Northern California is using that, so as soon as they get an alert, all the trains stop.

Sources:

Boston University

Provided by the IKCEST Disaster Risk Reduction Knowledge Service System

.

Comment list ( 0 )